These are dark times. The winters never end. Light has fled to caves, to the hearts of the humble, to foreign soil. The light has gone and things have become estranged; bright colors have bled to grey, have disappeared entirely. The shadows that accompanied forms have faded and everything seems alone and desolate. It is a world of loneliness and broken hearts. A destitute world without hope, without any call to unity, and above all a world indisposed to transcend itself and make sacrifices that will reconcile those at odds, unite them, and make it loud and clear that joy and fulfilment can be created in this chaos.

In a world such as this, the world of saints is a spark that keeps the reality of light alive in the darkness. The world of saints stands its ground unassumingly in the chaos of fragmentation, looks around lovingly, opens its tireless arms and embraces it all. It parts its lips and whispers a few meaningful words, an apology, an “I love you.”

Whenever I am asked to paint a saint, I become frightened. It is not that I lack sufficient knowledge of the art’s tremendous secrets; it is not that I do not know the complexities of lines or secret relationships of colors. It is not the technical aspects of egg tempera and everything else entailed. My fear runs deeper, is more substantial. What torments me is doubt, my distance from the light, my scant empirical knowledge. In the end, I cross myself and dare to embark on my journey to Ithaca, to a known unknown motherland. I dare to begin a journey in which I can learn, savor and describe all at once. Since painting is a journey of knowledge and experience and light when it is made with fear and passion and a sense of the distance at which one’s heart lies from the light.

The function of saints in a fragmented world

In a world of shattered figures, scattered relationships and orphaned hopes, saints are the light that brings unity and consolation to all who ask for it, for as long as they ask for it. And this precisely is what I wanted to convey when I began to paint this series of Athonite elders. I did not want it to be simply a series portraying their figures, but nor did I want it to be an attempt to render in visual form abstract concepts such as sainthood or deification. What I wanted was to demonstrate the ecclesiological aspects of their icons, the function of saints in a fragmented world in which they, too, lived and continue to live. A world which they loved through their love for Jesus Christ. A world which they transformed in a big or small way with their love, with their sacrifice, with their unobtrusive participation in life.

What I therefore intended in all my art was to record a system of relationships. How the saints related to Christ, how they related to creation, to other people, and to us, the viewers of their icons, who are called to be saints.

All these relationships had to become shapes and colors, so that they could become an aesthetic experience for the viewers who communed with the icons, thereby becoming knowledge and a call to repent, a move towards life as a society.

I chose the egg tempera technique. A wood panel as the substrate and hand-made paper for the ground on which the icons would be painted. I wanted a fine roughness, a more natural effect than would be produced by the indifferent glossiness of a gesso surface. I did not rely on the shiny, artificial support of gold leaf. The colors sufficed to render the simplicity of the ascetic elders’ lives.

Athonite elders

At night, I read about the lives of many Athonite elders. I chose those that moved me the most, with no other criterion driving me. And then I began to paint.

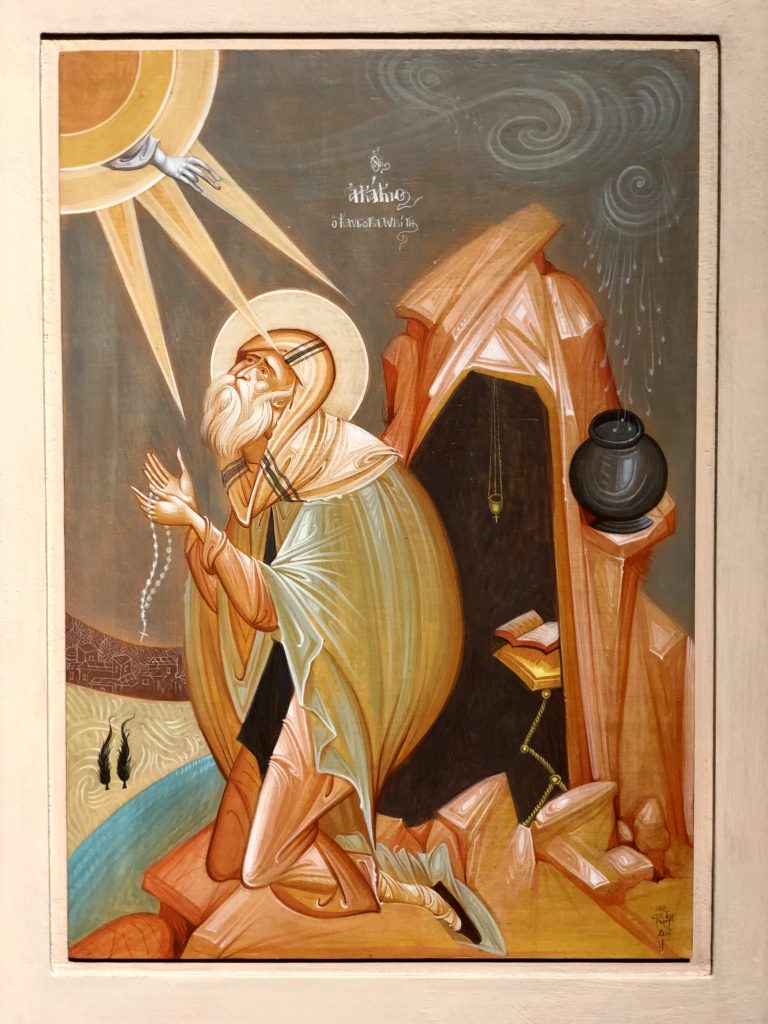

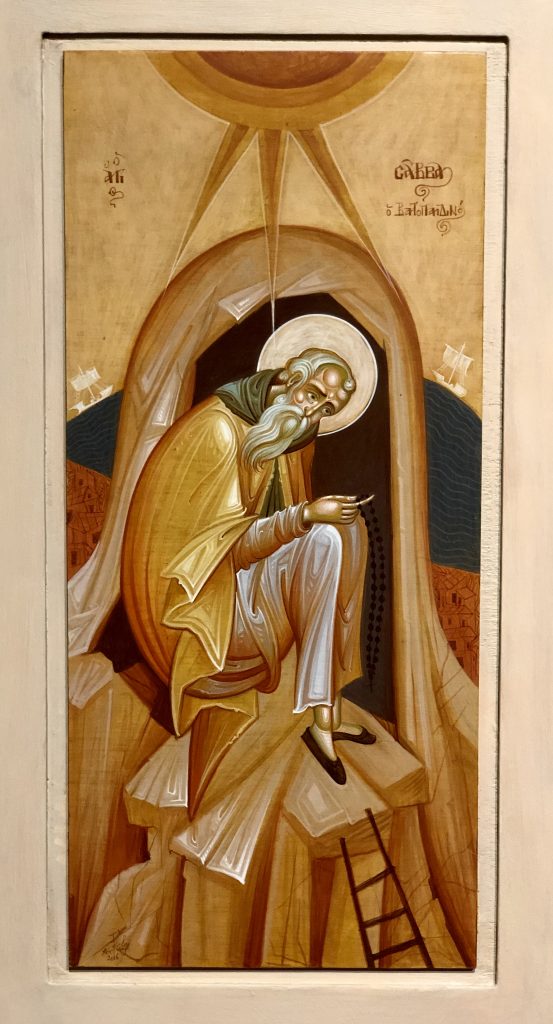

Two groups were formed. One contains eleven icons, which I would say are more narrative. The saints in this group are in prayer, addressing Christ and through their own love seeking His love. Portrayed in a secluded landscape, the supplicant saints are far away from the worldly cities that shimmer somewhere in the distance, painted without any plasticity or motion, without any energy or passion for union and life. In almost all the icons, ships cross the seas, signs of the mutability of human things and people’s ongoing, agonized search for life. And all around, fish and untiring, innocent trees stand tall in praise to the creator, accompanying the prayers, taming the anxiety and sweetening the light, united in the light of God’s presence.

The second group has ten bust-length icons of saints. Here the saints face us and want to connect with us; they crave to meet us and speak to us about Jesus Christ’s love, which unites the world and expels the fragmentation and division that death brings. In these icons, I mostly strove to exhibit, to show the ecclesiological function of icons. Here, the narration is not about the saint’s relationship with Christ or to a historical event, but rather attempts to bring into communion the saints with the viewers, be they believers or not, and with the world entire. Following the traditional artistic philosophy, these frontal portraits show how the Church sees relationships and life as a relationship, as a union of everyone and everything in Christ.

In these miniatures, the landscape and its elements are often rendered decoratively, as a design or textile on a monochrome plain, for the world to show a gem that is embellished by the presence of the saints and which in turn embellishes their presence. Place loses its significance, giving prominence to the saint’s human form, making it a living presence unconfined by the limits of space and time.

In any event, the tools and technique employed throughout the series were that of Byzantine painting and its tricks. The rhythm and handling of color as light.

The energy of the elements

Everything in the icons was designed in such a way as to follow axes that run crosswise, at times crooked and at other times curving and winding, so that there would be a dynamic equilibrium and unity through the energy of the elements, rather that an inert and static portrayal. Thus, all the elements in the icons, and ultimately the icon itself, become an expression of a unified reality of reconciliation, peace and love, which are heavenly qualities.

In this way, the icon becomes a manifestation of Orthodox ecclesiology and a visual actualization of the “unity of all.”

This unified artistic form is presented to the viewer/world through the artistic treatment of the icon’s elements and with the aid of rhythm. Therefore, with the appropriate perspective drawing, the order of colors and their tonal transitions, the Icon is cast into the viewers’ space-time, enters their space-time and becomes the present, bringing the qualities of heaven to the here and now. The icons thus bear witness to the Kingdom of God.

George Kordis

Athens, April 2017

Leave a Comment

You must be <a href="https://poetics.holyicon.org/wp-login.php?redirect_to=https%3A%2F%2Fpoetics.holyicon.org%2Fthe-light-of-the-world-pictorial-solace-with-icons-of-saints-of-mount-athos%2F">logged in</a> to post a comment.