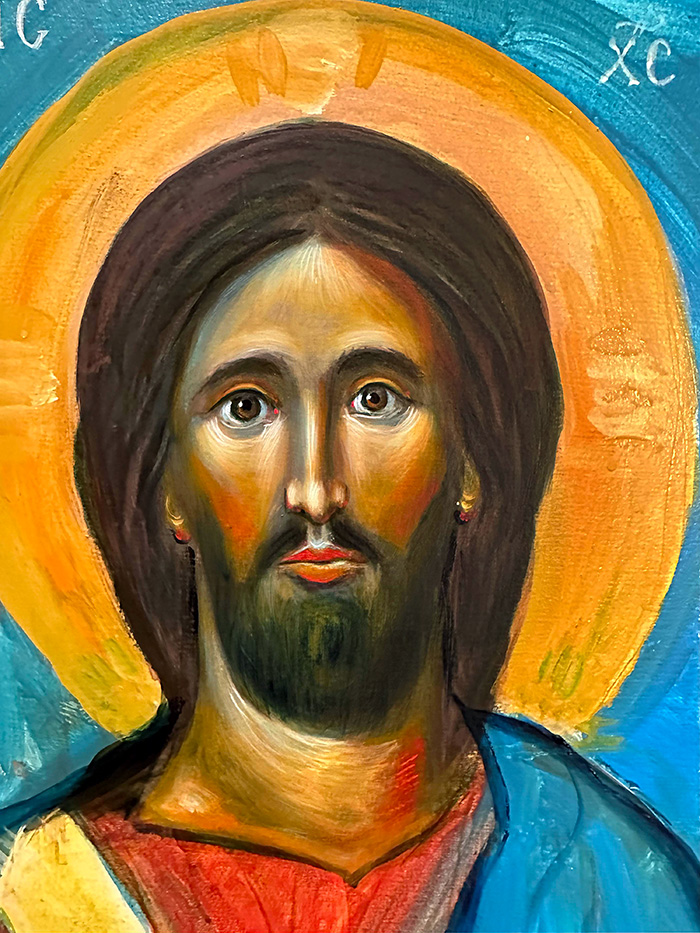

Exploring the Depth of Christ’s Look in the Iconography school of Bishop Maxim

by Fr. Stamatis Skliris

This icon of Christ belongs to the icons that present Christ with love and concern for the specific person, you and me. We achieve this mainly with wide-open eyes that care about us. It is a subtle movement beyond the Paleologian school of the almighty Pantokrator, here, with “thearchic weakness” (θεαρχική ἀσθένεια—the term by Dionysius Areopagite). In other words, the Pantokrator humbles himself with His image before the specific man with his particular passions and weaknesses. Out of love and identification with the humbled ontological concrete man, He who transcends suffering as God nevertheless willingly humbles himself and takes on human passion. It is a profound theology of the thearchic weakness that gave birth and developed (with “Justin’s” roots, that is, of Fr. Justin Popovic, who always presupposed a Christ who cares for man and who willingly humbles himself for him) the theology of “thearchic weakness.” Bishop Athanasios Jevtic loved the hymn of St. Basil the Great: “What shall we render unto the Lord for all He hath rendered unto us? For our sake, God dwelt among us; for our corrupted nature, the Word became flesh and dwelt within us; unto the ungrateful, He is the Benefactor; unto prisoners, He is the Liberator; unto those who sat in the darkness, He is the Sun of justice; the path unto the Cross; the Light unto Hades; Life unto death; Resurrection for the fallen: to Him, we cry out: ‘Our God, glory be to Thee!’” (Octoechos, tone 7)

The fact that the school of Maxim-Stamatis starts from an all-powerful God voluntarily becoming poor saves this school from anthropomorphism, Arianism, etc., because in principle, it is God Almighty, and what suffers is a passion born of the omnipotent voluntary movement. So, it is not a question of weakness inherent in God’s nature but of free movement toward weak man. It is of the Will and not of God’s nature. This Will is a loving will, and therefore, we hold the love (theia thelesis = divine Love, identified), which is expressed in the loving gaze, and we illustrate innocently and with divine dignity the Divine Passion. So, in God, there is a loving movement toward man. We could… “stretch” it, as our Elder Athanasius Jevtic would say, and say, God has only one, he has only one movement and will, the love for man, whom he wants to save, for to save in this way the whole creation, which is summed up in man!

In this look of Christ, Bishop Maxim expresses all the logoi of St. Maximus the Confessor. To put it anthropopathically, Christ’s gaze is as if envisioning the end of the adventure of divine love. This “that all of them may be one” (Jn 17:21) is the body of Christ that we taste in the Holy Eucharist and represents in temporal history everything that will exist and will not perish. This look of the many Christs of Bishop Maxim is the look of contingency, of waiting for the end; it is a pictorial eschatological look of God toward creation. It is not the gaze of God itself, but the gaze that the iconographer Bishop Maxim draws on the image of the God-man to theologize through the Image about God’s love for the referent man. Look, I beseech You, once more into the gaze of the God-man in the picture, and then look at the people around You. They look at each other very specifically, intra-temporally, i.e., very instantané. God looks very deep into the infinite depths of existence, which are beyond the horizon of horizons of temporality, as we say in the Eucharist, forever and ever.