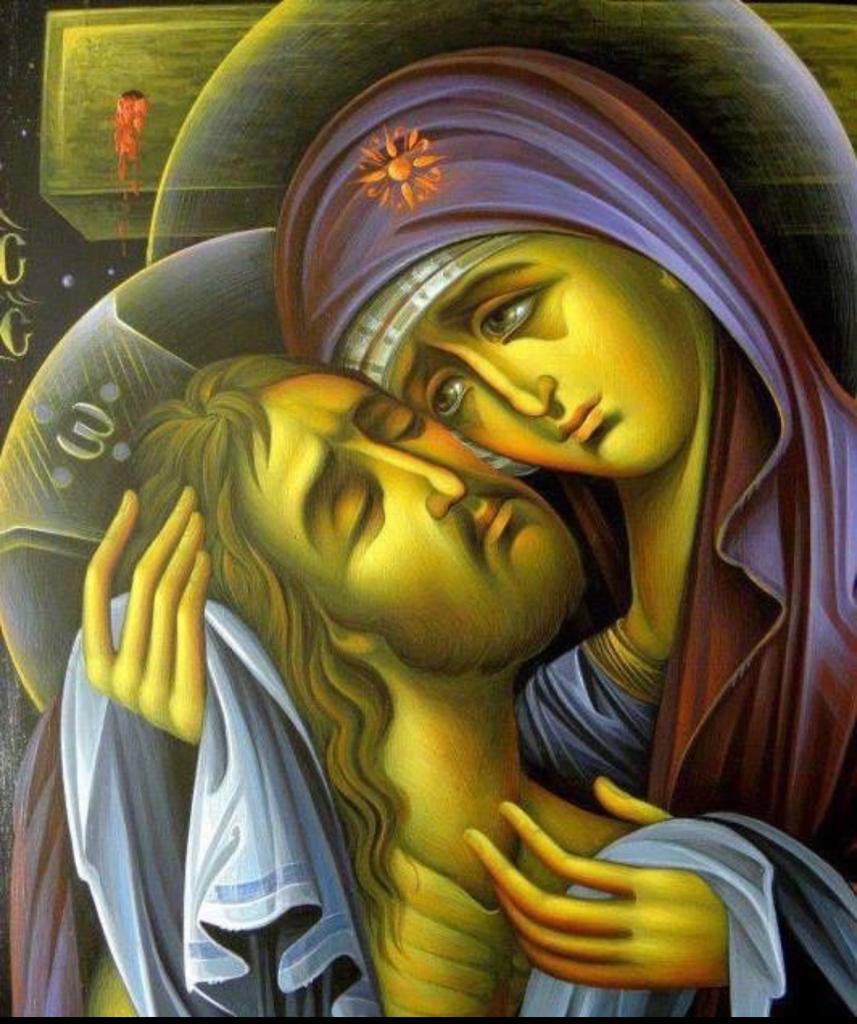

The last icon, of the grieving Theotokos and Christ, I do not know who it is from, but it is one of the most poignant I’ve ever seen. For me, it manages to convey something of the deep grief and the love between them at a depth and fineness that conveys something of the mystery of incarnation and sanctification which is the essence of iconographic purpose.

The departure from the centuries-old traditional style of iconography was shocking to me at first. But as in these icons, I have noticed that just as there exists a definite theological ‘canon’ that distinguishes byzantine iconography from western sentimentalism and/or realism in its ability to convey the unique truth of Orthodoxy, a similar ‘canon’ can be articulated which distinguishes “comic art” and ‘abstract art” from images that manage to depart from the traditional byzantine form while conveying Orthodox Truth of dialogue with the reality depicted, without distorting it or eclipsing it by their style of form and color. It is something the Impressionists managed to do in their time in respect to the natural world.

I am reminded of how blues and jazz emerged, departing from the ‘well-tempered clavier’ and were threatening and unfamiliar to people initially. Perhaps this iconographic renaissance is evidence of Orthodoxy in dialogue with contemporary culture in such a way that it remains itself while embracing elements in a new way that changes both. This could not have happened if the Impressionists had not done the same in the field of Western art departing from the control of the academicians who kept reinforcing the old school.

Father Stephen Muse